In The Shadow of Markham

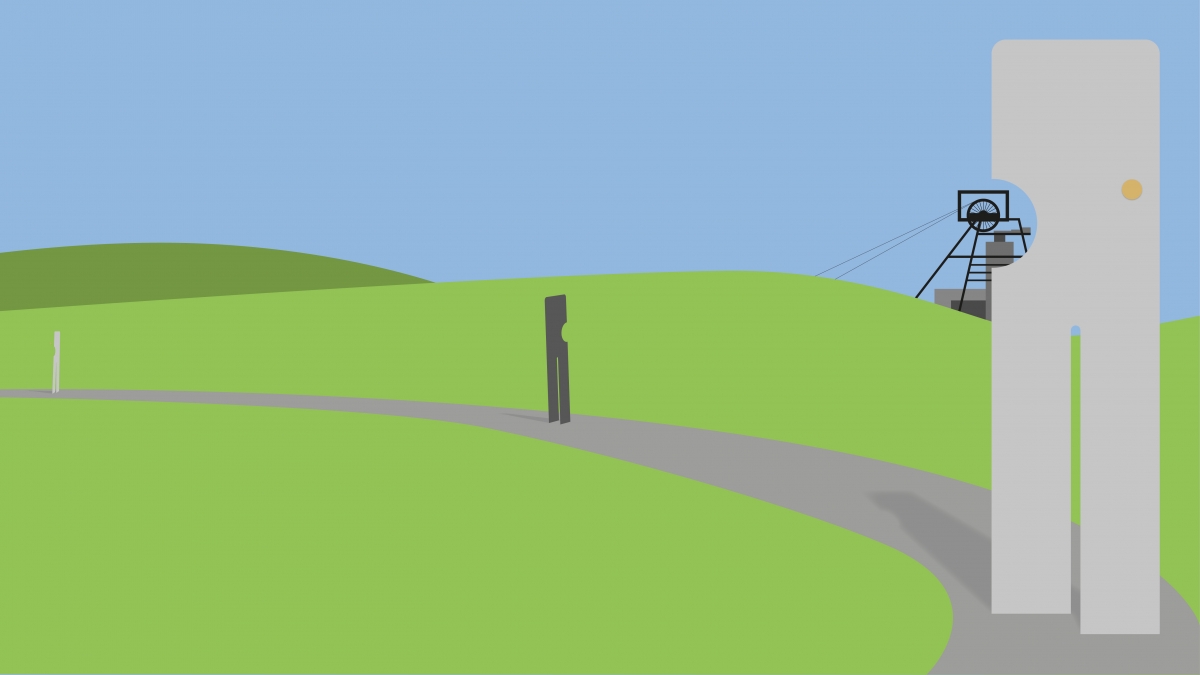

Born in 1962 I grew up in Duckmanton, and for many years the view from my bedroom window was completely dominated by Markham colliery, its huge brick built chimney, the headstocks, the winding houses and countless other mining specific buildings.

At night the scene was quite stunning, the pit head illuminated by an array of bright yellow and orange lights, highlighting tiny details in the silhouettes, whilst plumes of smoke and steam softened the outlines, and blurred the imposing spoil tip landscape behind.

Born the son of a Markham miner, every aspect of my childhood was in some way touched by the colliery.

Like many others, dad worked three shifts in rotation...days, afters’ and nights, while mum’s predominant role was to bring up my older brother, myself, and look after the house...as a young child, it appeared everyone’s parents in the village did the same.

Every day we would see men trudging wearily up Markham hill at the end of another shift their hands, and faces etched with ground-in coal dust, and clutching empty grey dented Acme snap tins.

The mine was the heartbeat of the village, providing guaranteed work for almost every family. Wages were not high, the hours were long, the work was physically draining, and it was dirty.

The colliery also afforded a huge degree of social support and cohesion that was vital for everyone. Amongst many other events, the Miner’s Welfare provided subsidised drinks and entertainment for members, a fantastic annual Christmas party for the children, a yearly day-trip to the coast...usually filling at least twelve coaches (each under the control of a ‘club committee member’ and laden with free pop and crisps for the children and a bottle of beer for the adults for the half-way stop).

Like all ‘pits’, Markham had a summer ‘shut-down’, the colliery serviced by minimal staff whilst the majority of the village travelled en masse to Skegness...more accurately the Miners’ Holiday Camp on Winthorpe Avenue between Skegness and Ingoldmells.

After a year of working so closely together in the grim dangerous underground reality that was mining...the chance to let off steam together for a whole two weeks and share some precious daylight provided brief respite during what for many was going to be their vocation for life.

The St John’s Brigade unit in the village was ‘Markham’ rather than Duckmanton, on sports day the at the village primary school the team names were named after local pits, Ireland, Arkwright and Markham...the colliery had its own football pitch, cricket pitch and bowling greens (in my early years). If you were unfortunate enough to acquire a minor injury of any sort in the home or playing out it was the medical centre at the pit head that provided treatment, strangely exciting visits as they exposed us at close quarters to the sounds and smells of a working colliery.

The only bars of soap we ever saw for many years were stamped with the letters PHB...and it was only later, on progressing to senior school, that I learned this was merely an acronym for Pit Head Baths.

It was convention that the destiny for the vast majority of boys in the village was a career underground, as generations had done before.

My father like most of his brothers had gone underground at Markham at 15, his own father had worked at the coal face either side of World War 1...a boy miner, sent to the trenches at Ypres...then returned with gas scarred lungs to serve out the rest of his working life at Markham, in backbreaking harsh conditions hundreds of feet below the ground. The ravages of mining and the battlefield robbed him of the chance to meet any of his grandchildren.

Dad eventually managed to gain promotion to an office based position in middle-management and, along with mum, encouraged my brother and I to work hard at primary school, pass our Eleven Plus exam and get a good enough education to break the cycle.

In July 1973, Markham was hit by its third major tragedy, when 18 men were killed, and 11 others seriously injured. Although only 10 at the time, I still clearly remember that day, the muggy overcast afternoon when so much anguish, uncertainty and unhappiness was so visible. Whole families stood at the pit head waiting for information, and rumours filtered up into the village. The national media covered the event, and for the very worst of reasons, Markham Colliery and Duckmanton were on the news. We, like everyone in the village, new someone who had been involved in the disaster, and it triggered many awful memories amongst grandmother’s generation who could still clearly recall the horror of the explosions in 1937 and ‘38.

A great deal of innocence and naivety was shattered that day.

A year later I passed my 11 Plus and went to grammar school. Like the vast majority of boys from the village I left school at 16 but never worked underground. To this day however, I fully understand and appreciate what Markham Colliery meant, and still means, to so many individuals, families and the whole community in Duckmanton and the surrounding area.

Steve Poole

Steve Poole is the Creative Director and owner of Yellow Spade Design.

Website: www.yellowspadedesign.com